Police Are Using DNA to Generate Suspect Images, Sight Unseen

The Edmonton Police Service in Alberta created its now-infamous rendering with a tool called Snapshot, which is sold by Parabon NanoLabs, a Virginia-based company that specializes in DNA analysis services for law enforcement.

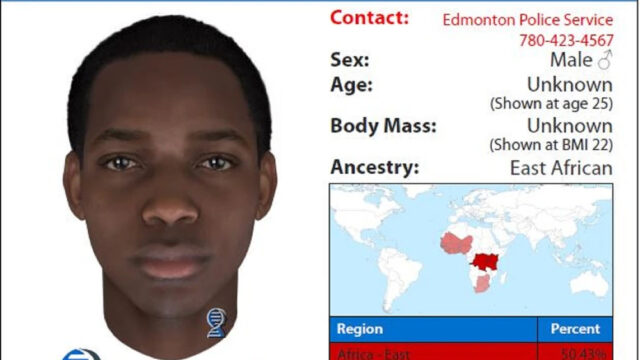

Snapshot can also generate a 3D image of the person’s face using its own physical description. This is concerning for several reasons. Not only does this create a feedback loop that only intensifies and exaggerates its own assumptions (kind of like that trend where TikTokers with themselves 10 times), but Snapshot is also forced to fill in gaps for which it has no data. Even if it doesn’t know the slope of someone’s brow, the shape of their nose, or whether the person has any moles or freckles, it has to make some kind of assumption to generate a complete image. (And before we go longing for the days of police sketch artists, remember that they, too, were filling in the gaps with what were guesses at best.)

The Snapshot rendering Edmonton PS disseminated last week, sparking public outrage. The image has since been removed from the agency’s website.

Edmonton PS that Snapshot images were only “scientific approximations” of a suspect’s appearance, and that the tool could not account for “environmental factors such as smoking, drinking, diet, and other non-environmental factors—e.g., facial hair, hairstyle, scars, etc.” The agency also said there weren’t any witnesses, CCTV, public tips, or immediate DNA matches to assist investigators after the crime took place. If that’s the case, that means investigators couldn’t confirm whether the rendering looked at all like their suspect. Every attempt investigators were making to arrest a suspect relied solely on DNA evidence, which as foolproof as it’s made out to be.

Edmonton PS isn’t the only law enforcement agency using Snapshot. Parabon’s website boasts partnerships with the Warwick Police Department in Rhode Island, the King County Sheriff’s Office in Washington, the Baltimore Police Department in Maryland, the Arlington and Fort Worth Police Departments in Texas, and many other agencies. As Snapshot’s use continues to spread, some worry the tool could result in false 911 calls or arrests. At best, it could stoke fear among civilians who think they’ve encountered a suspect; at worst, it could perpetuate racial biases that paint certain races in a criminal light or assume people of a particular race all look the same.

Following public outrage over its use of Snapshot and its dissemination of a suspect image—a 3D rendering of a Black man based on very limited physical data, as well as the vague assertion that he had an accent—the Edmonton PS took the image down last week. “The potential that a visual profile can provide far too broad a characterization from within a racialized community and in this case, Edmonton’s Black community, was not something I adequately considered,” said Enyinnah Okere, COO for the Edmonton PS Community Safety and Wellbeing Bureau, in a . “There is an important need to balance the potential investigative value of a practice with the all too real risks and unintended consequences to marginalized communities.” Okere went on to say the agency would be reconsidering the means by which it chooses to engage with new technologies. But will other agencies do the same?

Now Read: