Plants Can Grow in Lunar Soil, But They Suck at It

Of course, they didn’t do it just to see if they could. The researchers—two horticulturists and a geologist from the University of Florida—tested the plants’ viability in lunar soil to hopefully benefit future Moon or Mars landings. Space-grown plants could potentially offer fresh produce, oxygen, and water recycling to astronauts conducting these missions. If really is in our future, space agriculture will need to step up its game.

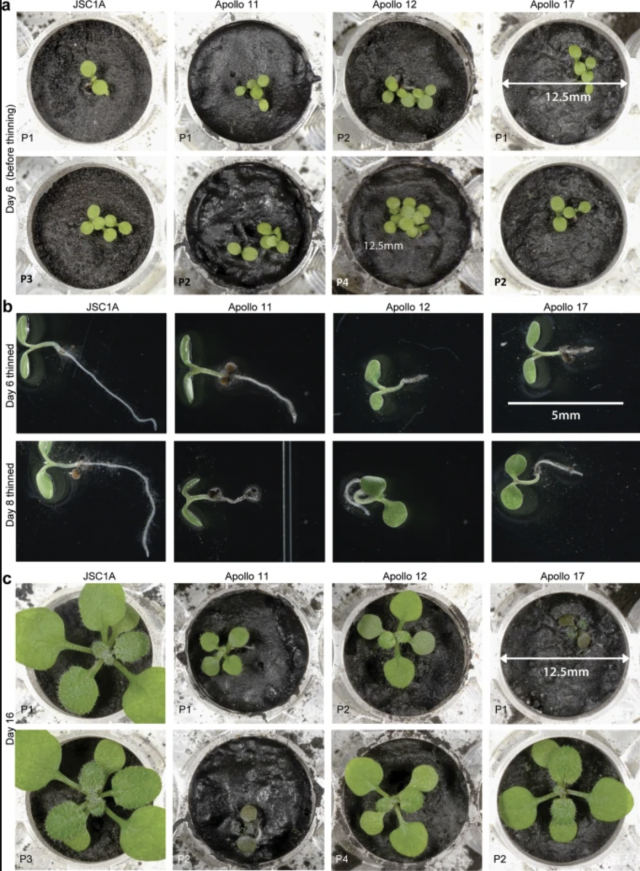

Lunar soil, or regolith, is a dusty byproduct of micrometeorites’ impact on the Moon’s surface. In samples obtained during the Apollo missions, the scientists planted seeds from Arabidopsis, a small flowering plant commonly used in biological experiments. The seeds sprouted within a week, but after that, confidence in their longevity waned.

(Image: Anna-Jean Paul et al/Communications Biology)

“Our results show that growth is challenging,” reads the , which was published in the journal Communications Biology this week. The plants grew slower and more erratically in the regolith than in a manufactured imitation soil referred to as JSC-1A; their leaves also took longer to unfurl. When the researchers removed most of the regolith seedlings from their containers, they found that the root systems were short, indicating stunted growth. This was not the case with the JSC-1A seedlings, whose root systems appeared generally healthy.

The plants grown in regolith also revealed their stress via genetic activity. Through transcriptome analysis, the researchers found that the regolith plants had activated genes related to nutrient metabolism, phosphate starvation, and aluminum toxicity.

Given the seedlings had such a hard time establishing themselves in regolith, it doesn’t look as though NASA will be opening a lunar greenhouse anytime soon. Even less likely is the possibility of growing extraterrestrial produce, since fruit and vegetable production requires significant amounts of energy and other resources that these plants simply didn’t have. But that isn’t to say either of those things are impossible—it just might take a bit of soil “optimization,” as the study’s authors optimistically point out.

Now Read: