Archeologists Discover 17th Century Remains of Suspected ‘Vampire’

The skeleton was found during an excavation near the city of Bydgoszcz. Early medieval graves had been uncovered in the area more than a decade before, when archeologists found jewelry, semi-precious stones, and remnants of silk clothing that had been buried with the deceased. A team from Poland’s Nicholas Copernicus University returned to the region this year to seek out artifacts from a 17th-century cemetery that had been damaged over the years by agriculture.

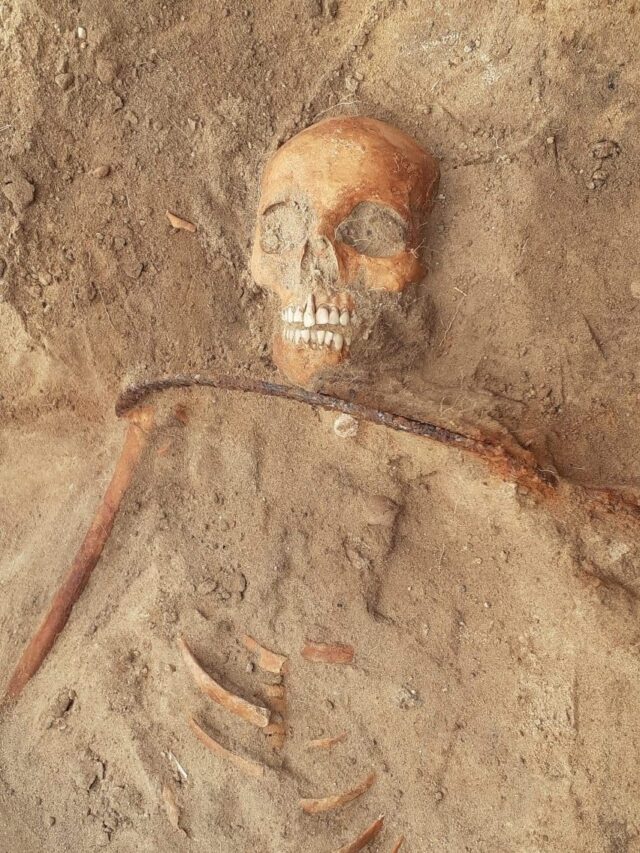

While human remains are to be expected in a cemetery, anti-vampiric customs are a little less common. The archeologists uncovered the intact skeleton of an adult female whose neck was pinned to the earth with the blade of a sickle. A padlock was also on the big toe of the skeleton’s left foot.

The team instantly recognized that the woman had been buried by someone (or a group of people) who had suspected she was a vampire. Both the sickle and the padlock were placed there by design: the sickle to injure or sever her head if she began to rise from the dead, and the padlock to “symbolize the impossibility of returning.” Her large, protruding front tooth also suggests the woman’s appearance had startled those around her, prompting cruel or superstitious people to assume she were a vampire or a witch.

(Photo: Mirosław Blicharski/Aleksander Poznań)

Back when people more habitually labeled their neighbors as supernatural beings, it was somewhat common to bury suspected evildoers in a way that prevented any potential return. This is why we often associate cinematic vampire-killing with a wooden stake through the heart. In specific German and Slavic cultures, suspected vampires would be decapitated prior to burial, with the head placed away from the body or between the feet. Some would be cremated, dismembered, or buried upside down for similar reasons. Still, a sickle placed over the deceased’s neck is a first for excavated Polish graves—even those from hundreds of years ago.

The suspected vampire from Bydgoszcz was, however, wearing a silk cap, suggesting some people in her community revered her. Silk was an extremely expensive material in the 1600s; to the archeologists, the woman would have needed to enjoy some form of elevated social or financial status to have been able to afford the cap (or receive it as a gift). While many of the details surrounding the woman’s social life might remain a mystery, her remains are headed to the university, where more information about her physical condition might be uncovered.

Now Read: