The vinyl industry is a mess — and this British company thinks it has the tech to fix it

Vinyl has undergone one hell of a renaissance. In 2006, the format was effectively dead. But since then? Vinyl records have experienced year-on-year growth, with the US alone clocking 41.7m units sold in 2021, a 45-fold increase from 16 years ago. While in Germany, sales went from 0.3m in 2006, to 4.5m last year.

Those numbers are somewhat misleading though — and their exuberance hides a darker story. Vinyl sales are strong, but the industry itself is at breaking point. From rising costs to a huge printing backlog, from mainstream label dominance to environmental concerns, and from material shortages to outdated equipment, records are being held together by a shoestring.

But — and there’s always a “but” in these pieces —wherever there’s a problem, there’s a potential to fix it. And, of course, to make some money along the way. In this instance, that mantle is being taken up by elasticStage.

Who or what is elasticStage?

Greetings, tech nerd!

Are you into gadgets? And apps? And other cool tech stuff? Then this weekly newsletter is for you.

Well, elasticStage is a British company co-founded by two Austrians: Steve Rhodes and Werner Freistaetter. Each of them have worked in the music industry as recording artists and behind the boards. The pair teamed up six years ago to create a machine they claim is the world’s first “on-demand” manufacturer of vinyl.

This isn’t Freistaetter’s first foray into this field of one-off record production either, as he founded Vinyl Carvers in 2002, a company that allows people to create a single vinyl disc. Rhodes and Freistaetter started elasticStage to take this idea further. While Vinyl Carvers targets DJs and people who want one or two songs on a disc, elasticStage wants to alter the entire sector.

It claims to have created a technology — which currently has a patent pending — that can not only be profitable from producing a whole record, but is also endlessly scalable. For all intents and purposes, they believe they’ve found the magic bullet that can transform vinyl. To find more out, I spoke with Rhodes, elasticStage’s CEO.

First off, Rhodes told me one needs to understand the current way vinyl is made to comprehend why a change is needed. Effectively, making a record is “one of the hardest things to do.” Vinyl was designed by “brilliant minds,” you know, the sort of people who work at NASA, lecture at Ivy League universities, and hold PhDs. It’s easy to forget how much of a marvel it is that a bit of etched plastic can produce such a beautiful sound.

The issue is the gap between the format’s heyday and its modern era. When records came back into the mainstream, many of the engineers responsible for designing and maintaining the machines that make them had retired or died. This means much knowledge was lost.

This has created our current situation, where there is a surging demand for vinyl, but a limited number of machines and places able to make them. Of course, there are new factories and machine-makers appearing — like the eco-friendly Deepgrooves in the Netherlands, the German-based Newbilt Machinery, and Viryl Technologies in Toronto — but this is a little like trying to plug a dam with cork.

There’s too much demand, a waiting list for many machines, and a huge financial outlay to buy one. Rhodes believes elasticStage can fix this.

Finding a new way to solve an old problem

Currently, vinyl is made in the same basic way it always has been. As succinctly as possible, it begins with a master disc. This is when a lacquer is cut, which is effectively carving music onto an acetate disc. After this comes the galvanics. Here, the lacquer is sprayed and, using electrolysis, is nickel plated. This creates a reverse of the record.

This step is repeated, creating a reverse of the reverse. This is then used to create the stamper, which, as it sounds, is the tool used to place the grooves onto a record, the physical representation of the music we hear. The stamper is heated up and pressed onto warm PVC (the substance vinyl is printed on), which is then cooled rapidly. Errors, as you can imagine, abound in such a fiddly process.

Of course, this is just a high-level overview, and there’s a lot more complexity. If you’d like to know a little more, this video is a useful guide:

One thing is clear with the above though: making vinyl records is expensive — both monetarily and environmentally. PVC isn’t a green material, and the energy costs of all that cutting, stamping, and heating are high.

In fact, the entire process is so intensive that it means for any sort of profit to be made, the minimum order for records is between 500 and 1,000 units. With its machine, elasticStage wants to completely change this.

A silver bullet… in the form of a rotating disc

Rhodes told me that the company’s machine uses “no chemicals,” and can produce a single record immediately — all while being profitable. He said there’s “no electroplating” and neither do they heat up plastic. Simply, users upload a lossless track online, which is then transferred (via the cloud) to the machine. It then quickly prints it with little hassle.

Despite this, he believes the records that elasticStage can produce maintains the vinyl sound people love. “The original way of making vinyl involves sound traveling through a magnetic field,” Rhodes told me, “we think that this is largely responsible for the ‘analog’ feel when people listen to vinyl records.”

He went on to say that elasticStage’s new technology also involves sound traveling through a magnetic field — and while they’ve “changed a lot of things,” they’ve made sure they’ve kept the “classic sound of a vinyl record.” Even more impressive, they claim to have “removed a lot of ‘negative’ elements from vinyl,” getting rid of things like a “[loss] of quality” or “loud pops and clicks.”

Now this is where I want to put a caveat. As much as I pressed for more information on how elasticStage’s technology works, Rhodes wasn’t able to give me specifics. He pointed towards the fact the company has a pending patent on its machine and doesn’t want any competitors to take its idea.

I understand the secrecy, but I do question why people haven’t cracked this case before. Companies like HD Vinyl tried (and failed) to revolutionize the technology, and there’s a part of me that worries whether elasticStage is making promises it can’t keep.

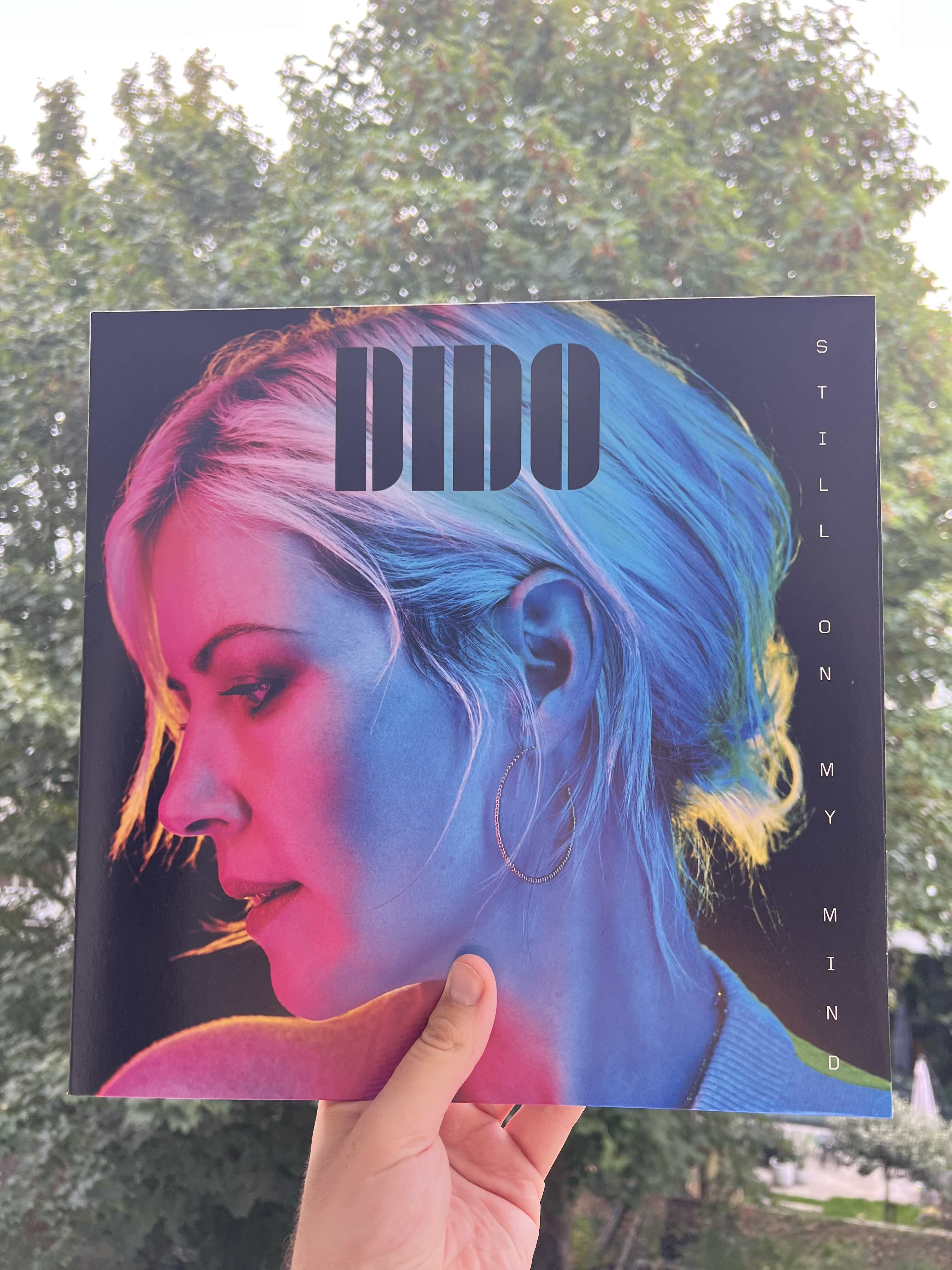

What I will say is that elasticStage shipped me a prototype of its record (a copy of Dido’s Still On My Mind if you’re interested) and it was damn impressive. It looked and felt like a regular vinyl, while the sound was great too — especially for something that’s not the finished product. So there is hope.

It’s clear that investors have some faith in the product, as elasticStage has raised £3.5m ($4.2m) in seed funding. And, honestly? It could be a good bet. If the technology delivers, it could not only be hugely profitable, but also put Europe at the heart of the vinyl industry.

Breaking down the business model

When speaking with Rhodes, he talked about three main business markets: small creators, regular printing, and compilations. The first is the rise of independent creators in the last few years. “About six years ago,” Rhodes told me, he had the thought that “the indies are going to take over.”

The increasing ease of at-home recording and explosion of technology meant he thought that “millions, if not hundreds of millions” of people would be creating music around the globe. Not only do “all these creators want to make a record,” he told me, but if you can be the person to serve them, you’ll automatically be the “largest label in the world.”

This is where the genesis of elasticStage began — and you can see the logic. At the end of 2021, Spotify announced in its Q4 earnings call that it hosted 11 million creators. This was an increase of 3 million from the year before.

While at the company’s 2022 Investor Day, CEO Daniel Ek laid out his vision for the company to have 50 million creators on the platform. The potential here is clear. If there are millions of creators passionate enough to put their music online, it goes without saying that many of these people would want their work to be on vinyl, even if it’s just for friends and family.

That is a huge market of hungry consumers ready to sell to. All they’d need to do is go on the elasticStage platform (I was shown a prototype of the site and it looked impressive), upload the cover of the vinyl, customize the inserts, the track-listing, and add their music. 48 hours later, their record would be arriving.

Major (label) potential

While the independent creator market is an exciting source of potential revenue, elasticStage isn’t content with that alone. “We want to build the go-to destination for physical records in the world,” Rhodes told TNW.

The company is already in discussions with major record labels and a big streamer. According to Rhodes, elasticStage is exploring whether its platform can be embedded into the app of a music streamer.

If they can manage such a feat, it’d be a goldmine. Large artists (like ABBA) are responsible for the lion’s share of vinyl sales, and if people can order their records directly from their streaming app using elasticStage’s platform, you have to believe it’ll lead to a lot of sales.

This can go even further. If deals can be struck with record companies, there’s the potential for elasticStage to be used to produce compilations. Imagine the appeal of putting your most listened to songs, or a collection of tracks you and your partner love onto wax.

What’s the future for elasticStage?

ElasticStage has its eyes set on the big time. It’s currently set on moving its production facilities from Germany into the UK. From here, it’s entering a trial run in 2023, with the aim of producing a million records that year. The year after, elasticStage plans on having large facilities in Europe and the US, and upping its creation and shipping capacity by tenfold.

Rhodes believes the vinyl sold by elasticStage will be in the region of £20 ($23 or €23) — with certain exceptions, obviously. In other words, records made with the technology will cost about the same (if not slightly less) than what’s on the market today.

Of course, the elephant in the room is the miraculous technology the company is currently patenting. I’d love to believe that producing good quality records this quickly is possible, but I’m going to withhold judgment until I see it at scale and know more about how it works.

It’s hard though not to be swayed by elasticStage’s mission. As Rhodes put it, the company wants to “make vinyl sustainable,” take away the pain of purchasing and producing them, and “make every record available.” That’s an admirable goal. And if it can achieve its mission, elasticStage will be responsible for dragging vinyl into the 21st century.